When your dirt bike engine roars to life, temperatures inside the combustion chamber can exceed 1,000°F—enough to melt aluminum components within minutes without proper cooling. The radiator isn’t just another component on your bike; it’s the critical heat management system that prevents catastrophic engine failure during demanding off-road conditions. Understanding how does a dirt bike radiator work empowers riders to recognize early warning signs of trouble, perform essential maintenance, and maximize performance during intense riding sessions. This knowledge separates casual riders from those who consistently keep their machines running at peak efficiency, avoiding the expensive repairs that come from overheating damage.

Unlike street motorcycles that often have consistent airflow, dirt bikes face unique cooling challenges with frequent stops, slow technical sections, and dusty environments that restrict airflow. The radiator works as part of an integrated liquid cooling system specifically engineered to handle these extreme conditions, maintaining optimal engine temperature whether you’re crawling through rock gardens or flying down fire roads. Without this sophisticated heat management, modern high-performance dirt bike engines simply couldn’t deliver their impressive power-to-weight ratios while maintaining reliability through punishing race conditions or weekend trail rides.

The Liquid Cooling System Explained

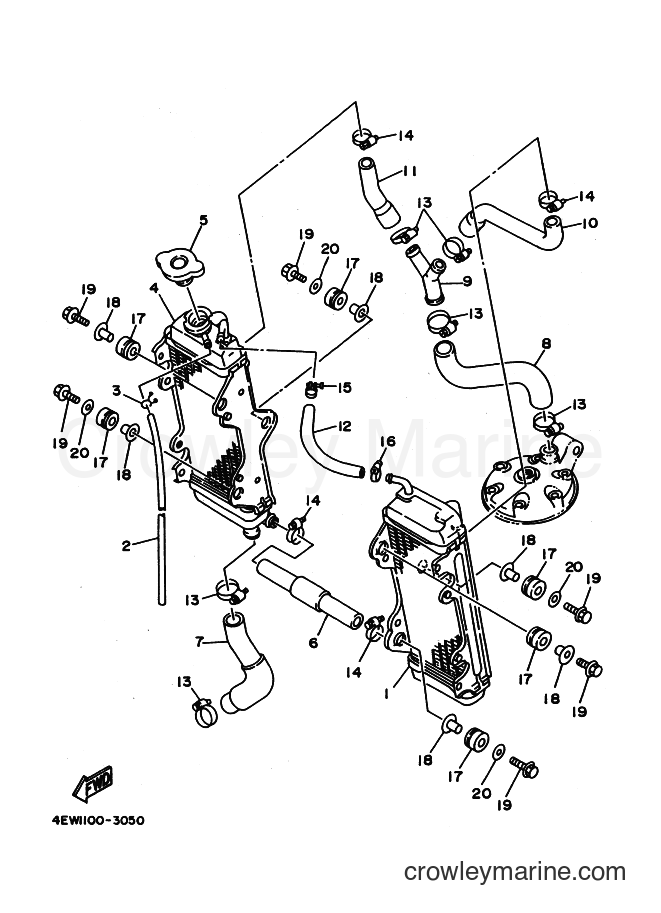

A dirt bike’s cooling system operates as a closed loop consisting of several interconnected components that work in harmony. The water pump, typically driven by the engine’s camshaft or crankshaft, circulates coolant through passages machined into the engine block and cylinder head. These internal passages surround the combustion chambers and exhaust ports, areas that generate the most heat during operation. As hot coolant exits the engine, it flows through upper radiator hoses toward the radiator core, where the actual heat dissipation occurs. The thermostat, a temperature-sensitive valve located near the engine, remains closed during cold startup to speed warm-up and opens once the engine reaches operating temperature (usually around 180°F), allowing full coolant flow through the system.

The radiator itself consists of a core with multiple thin tubes surrounded by cooling fins, all typically made from lightweight aluminum to meet dirt bike weight requirements. Hot coolant enters the core through the upper tank and flows through the tubes while heat transfers to the fins. Ambient air moving through the fins, whether from forward momentum or electric fan assistance, carries away this thermal energy. By the time coolant exits through the lower tank and returns to the engine via the water pump, its temperature has dropped significantly, ready to absorb more heat in another cycle. This continuous process maintains engine temperature within an optimal range, typically between 180°F and 220°F depending on the bike’s design.

What Happens When You Accelerate

During hard acceleration, combustion temperatures spike dramatically, requiring immediate heat transfer. The water pump spins faster, increasing coolant circulation rate through the system. Simultaneously, forward motion creates greater airflow through the radiator core, enhancing heat dissipation. Modern dirt bikes often feature temperature sensors that monitor these rapid changes and may activate cooling fans even during riding if temperatures approach critical levels. The thermostat modulates flow based on temperature demands—opening wider during high-load conditions and partially closing when less cooling is needed. This dynamic response prevents both overheating during hard riding and overcooling during idle periods, keeping the engine in its performance sweet spot.

Common System Failures During Riding

Riders often encounter cooling issues when riding through deep mud or water crossings that coat the radiator fins with insulating material. Without immediate attention, temperatures can climb rapidly as heat transfer becomes restricted. Another frequent problem occurs when debris like leaves or plastic bags become lodged against the radiator, creating a barrier that prevents proper airflow. In extreme cases, riding through extremely cold conditions can cause the thermostat to remain partially closed longer than necessary, leading to engine temperatures that stay too low for optimal performance. Recognizing these situations and knowing how does a dirt bike radiator work helps riders take preventive action before damage occurs.

Radiator Construction and Key Components

Modern dirt bike radiators prioritize cooling efficiency while meeting strict weight limitations, leading to specialized designs that differ significantly from automotive radiators. The core typically features a cross-flow or down-flow configuration, with aluminum tubes brazed or welded to aluminum end tanks that distribute incoming and outgoing coolant. These tubes often include internal turbulator fins that increase coolant turbulence, improving heat transfer efficiency by disrupting laminar flow along tube walls. The external cooling fins increase surface area for air contact, with fin density carefully calculated to balance airflow resistance against heat dissipation needs.

The radiator cap plays a crucial but often overlooked role in system pressure. By maintaining pressure between 10-15 PSI, the cap raises the boiling point of coolant, allowing the system to absorb more heat before boiling occurs. This pressurized system also helps eliminate air pockets that could cause hot spots in the engine. Coolant reservoir tanks, usually translucent plastic mounted near the radiator, provide a visible coolant level indicator and accommodate thermal expansion as coolant expands and contracts with temperature changes. Many dirt bike radiators also incorporate integrated oil coolers or transmission coolers in performance applications, combining multiple heat exchangers into a single compact unit.

Why Aluminum Dominates Dirt Bike Radiators

Aluminum has become the standard material for dirt bike radiators due to its excellent thermal conductivity, lightweight properties, and corrosion resistance when properly treated. Compared to traditional copper-brass radiators, aluminum cores weigh approximately 30% less while providing equivalent cooling capacity—a critical factor in off-road competition where every ounce counts. Aluminum also withstands vibration better than copper, resisting fatigue cracks that can develop during rough riding conditions. Manufacturers use specialized alloys and manufacturing processes like vacuum brazing to create joints that maintain integrity under thermal cycling and mechanical stress. The trade-off is that aluminum requires compatible coolants with proper corrosion inhibitors, as improper mixtures can lead to rapid deterioration of internal passages.

The Cooling Fan and Airflow Management

Electric cooling fans have become standard equipment on most modern dirt bikes, providing critical cooling assistance during low-speed or stopped situations where natural airflow is insufficient. These fans are typically controlled by a temperature switch or ECU sensor that activates when coolant temperature exceeds a set threshold, usually around 220°F. The fan draws air through the radiator core, creating negative pressure that pulls ambient air across the cooling fins. When the temperature drops sufficiently, the fan shuts off to conserve battery power and reduce noise.

Airflow management extends beyond the fan to include radiator shrouds and louvers that direct air efficiently through the core. The space between the radiator and the bike’s frame often includes rubber bushings that isolate vibration and allow for minor radiator movement without cracking. Many riders install radiator braces or guards to protect against rocks, debris, and crash damage—radiators are vulnerable components positioned at the front of the bike. Proper shroud sealing is essential; gaps around radiator edges allow air to bypass the core rather than flowing through it, dramatically reducing cooling efficiency. Some competition-focused riders install aftermarket high-flow radiators with increased coolant capacity and enhanced fin designs for demanding conditions.

Optimizing Airflow for Different Riding Conditions

Serious riders understand that radiator positioning and airflow management require adjustment based on riding conditions. In extremely dusty environments, many install mesh screens that protect against large debris while maintaining sufficient airflow—though these require frequent cleaning to prevent clogging. For desert racing where temperatures regularly exceed 100°F, riders often remove unnecessary body panels to maximize airflow through the radiator area. In contrast, winter riders in cold climates sometimes use radiator covers to prevent excessive cooling that keeps engines below optimal operating temperature. The most sophisticated setups include adjustable fan controllers that allow riders to set custom activation temperatures based on anticipated riding conditions, giving them precise control over the cooling system’s behavior.

Heat Transfer Principles at Work

The radiator’s operation relies on fundamental thermodynamics governing heat transfer between the coolant, radiator material, and surrounding air. Conduction transfers heat from the hot coolant through the aluminum tube walls to the external fin surfaces. Convection then moves heat from the fin surfaces to the passing air stream, with forced convection from the fan and motorcycle movement being far more efficient than natural convection. The large surface area provided by fins maximizes this convective cooling, while thin tube walls minimize thermal resistance between coolant and air.

Coolant chemistry significantly impacts heat transfer efficiency. Water provides excellent thermal properties but freezes at 32°F and boils at 212°F, making pure water unsuitable for dirt bike applications. Modern coolants blend water with ethylene glycol or propylene glycol, raising the boiling point, lowering the freezing point, and adding corrosion inhibitors that protect internal passages. However, pure water actually transfers heat more efficiently than coolant mixtures, leading some racers to use diluted mixtures or water with additives for maximum cooling performance, accepting the corrosion and freeze protection trade-offs. The ideal coolant mixture for most dirt bike applications is a 50/50 blend of coolant and distilled water, providing a good balance of heat transfer, corrosion protection, and temperature extremes coverage.

Troubleshooting Common Radiator Problems

Radiator issues typically manifest as overheating, visible coolant leaks, or deformed components. Coolant leaks at hose connections often indicate deteriorating clamps or cracked hoses that need replacement. Internal leaks, where coolant enters the combustion chamber, produce white “sweet-smelling” exhaust smoke and may indicate a blown head gasket or cracked cylinder head. External coolant puddles beneath the bike suggest holes or cracks in the radiator core, often caused by rock impacts or corrosion from using incompatible coolants.

Overheating problems require systematic diagnosis. Start by checking coolant level in the reservoir, ensuring the system is properly filled with no air pockets. Inspect hoses for collapse or restrictions that could impede flow. Feel upper and lower radiator hoses during operation—the upper should be hot while the lower remains noticeably cooler when the system functions properly. If both hoses feel equally hot, the thermostat may be stuck open, preventing the engine from reaching proper operating temperature, or flow may be restricted elsewhere. A stuck-closed thermostat causes immediate overheating as coolant bypasses the radiator entirely. Testing involves removing the thermostat and suspending it in boiling water; a functioning thermostat should open as the water approaches 200°F.

Maintaining Optimal Radiator Performance

Regular maintenance extends radiator life and prevents cooling system failures. Before each ride, inspect coolant levels and check for leaks or damage to hoses and connections. Periodically flush the cooling system to remove accumulated contaminants and old coolant that loses effectiveness over time. The recommended flush interval varies by usage—aggressive racing or frequent muddy conditions may require more frequent service than casual trail riding. When refilling the system, use the manufacturer-specified coolant type and mixture ratio, and bleed air from the system properly to prevent hot spots.

Radiator cleaning significantly impacts cooling efficiency. Mud, dust, and debris packed between cooling fins restrict airflow and insulate heat. Use soft brushes or compressed air to clean debris from the fins, working carefully to avoid bending or damaging the delicate fins. Bent fins can be straightened with a fin comb or flathead screwdriver, though excessive bending compromises structural integrity. Inspect radiator mounts for cracks or deterioration that could allow dangerous movement during riding. For riders in extremely dusty or muddy conditions, radiator guards provide essential protection while maintaining some airflow, and periodic removal for cleaning prevents the buildup that causes overheating during extended rides.